|

| photo - Tatzu Nishi |

In Pride of the Cities, famed New York City short story writer O.Henry hinted at the snobbishness of some people in New York looking down on the west side of Manhattan in the early part of twentieth century.

"I!" said the New Yorker. "I was never farther west than Eighth Avenue. I had a brother who died on Ninth, but I met the cortege at Eighth. There was a bunch of violets on the hearse, and the undertaker mentioned the incident to avoid mistake. I cannot say that I am familiar with the West."

And although the Upper West Side of Manhattan was in full bloom of development, there were still empty lots to the right property not melded with the right building idea etc.

Diamond Jim Brady pulled up stakes in a bachelor pad apartment on 57th Street in 1900 to buy a four story brownstone off Central Park West at 7 West 86thStreet and furnished or had it furnished by a decorator in every strange dusty and obsolete item of the imminently about to arrive deceased Victorian Era circa 1901.

So too having been born around the west side docks downtown on Cedar Street, I believe Diamond Jim felt more comfortable with the professional classes that seemed to gravitate up Broadway to the Bronx instead of situated near the Uber-Rich building castles on Fifth Avenue.

That and I think a self-made millionaire like Brady preferred not to see the rich on the East Side. He even though he did not drink alcohol he could only mingle with those 400 or so rich elite types on a temporary basis in the Plaza bar or bar at the Waldorf (hyphen) Astoria as some referred to that famed bastion of the well to do.

That in search of an identity would not come before Mayor LaGuardia, Columbus Circle as Gateway to that upper west side was more of circus in attitude and carnival appeal to tourists from the 1880s until the 1930s.

Big anchor buildings of the modern era were not yet present in this traffic circle and lower case lower class entrance to the big park – Central Park.

Different as night and day the entrance at Fifth and West Fifty-ninth Street and Fifth Avenue in the shadow of the Plaza Hotel compared to six dissected points of three streets intersecting – Broadway, Eighth Avenue and West Fifty-ninth Street – all wrapped around the Columbus (an Immigration / Assimilation Symbol) statue on top of its memorial stone column.

Postcards of the time would indicate this area as a tourist spot. With its entrance to Central Park near the west side Seventh Ave subway it was probably the most visited subway stop on any given weekend or Summer weekday to compete with any stops downtown, the heart of the Maritime Shipping and Financial Center of the city.

The very nature of its being was as staging area, transient lay off spot, up from the newly emerging Time Square fifteen blocks south but also as a local area of saloons, shops, entertainments, theaters to capture the Tourist Dime or Nickel.

|

| Touristas |

|

Postcard Viewing South Along Broadway circa 1910

|

|

1905 Columbus Circle – Viewing North – Park Entrance (right),

Central Park West (N.Eighth Ave.) and Broadway (left) |

|

| Columbus Circle NYC (circa 1906) Shadow of Columbus Statue on Monument (bottom left) (Public Domain) |

From his father he learned radical humanist ideas about harmony, balance, brotherhood and socialized land use like as in a kibbutz for some modern comparison of radical back then self-actualization - and from his grandfather he learned practical basics of architecture and engineering in the family business and or sideline of running a government owned iron foundry back in France.

Being too liberal or too intelligent to live in a dumbed down France after the shit hit the fan in 1848, the Gengembre family emigrated to America to live life with in pre-civil war pre-rust belt Ohio and western Pennsylvania. Fast forward a decade and with some U.S. Government Patent buying money, $120,000, to help the civil war effort against the southern states, young inventor Philip Gengembre did a European tour to drink in beauty, architecture and current radical thinking on the continent, and then settled into post-civil war Manhattan to raise his young family.

He attached himself to an older Architect for some polish and sabe on his self-learned architecture thing and set out a shingle in old New York to practice his desired trade.

Philip added his maternal grandmom’s maiden name (Sophia Hubert - his mother's maiden name Marianne Farey - both English) btw to his own in order for his A-merican customers that had trouble pronouncing his own – kind of like a self-inflicted cutting pre-Ellis Island nasty chalk mark so to speak to get used to the new land’s ways and all that.

Truth of the matter, Hubert had an idea to help lower middle class workers, as in the clerk class to get together, buy land, build an apartment building and share the wealth of the profits of renting out 10-20 percent of the apartment units and actually giving dividends back to the original limited shareholders that bought a right to an apartment in that building in this new radical non-bank way, use of home comfort instead of maximum profit, for people living in a land starved environment like New York.

Banks at the time did not want to be pushed out on the profit thing but the clerks with their limited means could not finance these worker projects by themselves. Exit stage left.

Then the middle class speculators took over and offered a set price on middle class co-op living arrangement in planned big spacious apartment buildings and it all went to hell as in any uncontrolled, unregulated financial situation and without banks in large part to monopolize the mortgage market so to speak.

Philip lectured on his concept borrowed from European Utopian ideas and experimentation and got the right sort of professionals, doctors, lawyers, architects, engineers, artists and started what were called “Hubert Home Clubs” and some of them actually started, succeeded and thrived in this new radical self-financing co-op apartment gimmick. Meanwhile at the ranch, big foreign speculators like José Francisco de Navarro were building Trump like Co-op Apartments and with Trump like pyramid financing.:

|

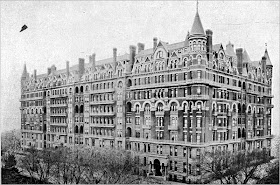

| Navarro "Spanish" Flats - S.E.Corner Seventh Avenue and West 59th Street |

Although first called the Central Park Apartments, they soon became known as the Navarro Flats or, sometimes, the Spanish Flats.

The buildings, each 13 stories tall, were named the Madrid, the Cordova, the Granada, the Valencia, the Lisbon, the Barcelona, the Saragossa and the Tolosa.

The sales brochure for the apartments, most of them seven-bedroom duplexes, listed them at $20,000 for corner units and $15,000 for those with only one exposure. Maintenance was $100 to $200 a month.

The architect, Hubert & Pirsson, staggered the floors so that the principal rooms, facing the street, had extra-high ceilings. It’s a comment on the times that the apartments had only two bathrooms each.

There were some particularly large apartments, about 7,000 square feet, with a library measuring 19 feet by 22 feet, a drawing room 17 by 39, a billiard room 18 by 24, and a dining room 16 by 31. “Not 10 houses in New York” have such a scale of entertaining rooms, said The Real Estate Record & Guide.

Unlike the cool beige brick and stone of the Dakota, the Navarro Flats buildings were hot-red brick set off against a wild cliff of stone-trimmed arches, turrets, gables and other features — an arrangement that Scientific American called “most unsatisfactory” in 1884. There were some Moorish details, but the buildings were also described as both Gothic and Queen Anne in style.

The buildings, each 13 stories tall, were named the Madrid, the Cordova, the Granada, the Valencia, the Lisbon, the Barcelona, the Saragossa and the Tolosa.

The sales brochure for the apartments, most of them seven-bedroom duplexes, listed them at $20,000 for corner units and $15,000 for those with only one exposure. Maintenance was $100 to $200 a month.

The architect, Hubert & Pirsson, staggered the floors so that the principal rooms, facing the street, had extra-high ceilings. It’s a comment on the times that the apartments had only two bathrooms each.

There were some particularly large apartments, about 7,000 square feet, with a library measuring 19 feet by 22 feet, a drawing room 17 by 39, a billiard room 18 by 24, and a dining room 16 by 31. “Not 10 houses in New York” have such a scale of entertaining rooms, said The Real Estate Record & Guide.

Unlike the cool beige brick and stone of the Dakota, the Navarro Flats buildings were hot-red brick set off against a wild cliff of stone-trimmed arches, turrets, gables and other features — an arrangement that Scientific American called “most unsatisfactory” in 1884. There were some Moorish details, but the buildings were also described as both Gothic and Queen Anne in style.

|

| Hawthorne Co-op by Philip G.Hubert (left) Next to Navarro Flats |

Looking west on northern sidewalk of 59th Street Transit System Survey – 1914 – photo by G.W.Pullis – From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYWT8IGN9&SMLS=1&RW=1032&RH=505#/SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYWT8IGN9&SMLS=1&RW=1032&RH=505&PN=1

Nobody has ever heard of Jose Navarro but because he, Philip Hubert, was the architect on the Big One that went down and turned speculators into “Hubert” haters ever since, it is little wonder why they have scraped his name off his buildings so to speak in the history books so to speak, that and only two or three of those early co-ops still stand in a city that consumes itself like a snake eating its own R/E tail.

Diamond Jim Brady’s brand new brownstone in 1900 got gobbled up into a typical big apartment building on CPW in something like 30 years.

Though in researching Philip Hubert, I have to wonder why so many give no mention of the one artist’s co-op on the emerging west side near Columbus Circle that was named after himself when writing about a litany of all his other dead extinct projects.

Perhaps the natural of “The Hubert” and its residents wanting anonymity, performed perfecting in that nobody was aware of it in the middle of the Columbus Circle Circus and poor people’s entrance to Central Park and general tourist chaos in hot steamy peak tourist seasons past.

Rather unassuming and looking so non-descript with what I would call Worker’s Modern – not “Queen Anne Revival with a touch of Victorian Gothic” - architecture of late nineteenth century urban America.

With its working class thrift in exterior materials, bricks, some terra-cotta, marble trims and iron work, you have a theme repeating many times with Philip G. Hubert – or at least with his Hawthorne 126-130 West 59th Street, Hubert 226-230 West 59th Street and Chelsea (Hotel) Co-op home / apartments 222 West 23rd Street.

The Hubert next to Gainsborough Studios on left, Circa 1920 - photo [Columbus Circle.] - From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York.

|

| Bromley Atlas of the City of New York 1922 |

The Hubert next to Gainsborough Studios on right, 1910- photo by Wurts Bros. - From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York

|

| George Henry Story - Self Portrait 1902 Gift to Metropolitan Museum of Art by Mrs. Henry Story 1906 Public Domain per Wiki Commons |

George Henry Story – Artist – 1835-1922

I started this research on Hubert based on the Obituary of George Henry Story, one time Treasurer of the Hubert Co-op Apartment Association. His NYT Obit in link below Oval Office Photo.

Other artists listing their home address or studio address as 226-230 West 59th Street over time besides G.H. Story are: Edward August Bell, Gifford Beal and Dwight William Tryon. Also a resident was a Wall Street lawyer named Lemuel Skidmore.

Other artists listing their home address or studio address as 226-230 West 59th Street over time besides G.H. Story are: Edward August Bell, Gifford Beal and Dwight William Tryon. Also a resident was a Wall Street lawyer named Lemuel Skidmore.

|

| President Obama Admiring George Henry Story Portrait of Abraham Lincoln in Oval Office West Wing White House http://thisculturalchristian.blogspot.com/2012/05/george-henry-story-american-artist-1835.html |

Story is pretty much a self taught jack of many trades who started out life in Hartford Connecticut and became a cabinet maker and frame carver. He ended up one day amidst his many travels renting space as an art portrait studio, in a corner of the Matthew Brady Photo Studio in Washington DC. That one day Brady with his hands full asked Story to help pose President Lincoln, run him through on the do’s and don’ts of posing for some minutes before an exposed negative in the camera.

From there Story was allowed access to Lincoln in the White House to make sketches which led to what he is most famous for in his paintings, his Lincoln Portraits, a dozen or so, one of which is in the White House.

His other portraits of Lincoln’s cabinet have yet to surface in Auctions.

He was curator of Painting at the new Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for seventeen years and temporary director for two.

There is a catalogue of responses to his letters to artists in the Met’s collection for biographical data and to catalogue all art in the collection.

|

| Metropolitan Museum of Art 1871 |

|

MMA circa 1880s

|

Philip G. Hubert with his Grandson Philip Hubert Frohman standing on the roof of the New York Riding Academy with the background of his masterpiece – the Navarro “Spanish” Flats.

April 23, 2016 Correction:

The correct

identity of the boy in this photo above has been identified to me as another

grandson of Philip Gengembre Hubert who

was Louis Henry Frohman, younger brother of Philip Hubert Frohman. The location of the

standing place of Hubert and his grandson Louis is the roof of The Sevillia

Hotel 117 W. 58th Street, a building of Hubert's design, also identified as both birthplace and

childhood home of Louis Henry Frohman

.

-4.jpg)

-5.jpg)

-6.jpg)

-7.jpg)

-8.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment